Introduction

Special effects, such as alien features, wound simulations, and aging, in film are often achieved by special effect prosthetics. These are cast out of silicone or foam latex and glued directly to the skin. Manufacturing special-effects prosthetics process can be time-consuming, inconsistent, and resistant to customization. First, the geometry is molded by hand, usually out of clay, onto a life cast of an actor or model. A mold is created out of plaster, and the clay is cleaned out. The lifecast and the outer plaster mold form a two-part mold into which either silicone or foam latex is poured. This process ensures that the prosthetics are well-fitting, smooth, and can capture detail at a high resolution, all necessary components for a prosthetic to look good on film.

SLA printing could offer several potential advantages over this manufacturing process. SLA printing is more easily and quickly changed than the molding process. In the molding process, any design changes mean the process must start from the beginning, whereas with SLA printing, only the CAD model needs to be changed. SLA printing may potentially take less time overall than the traditional molding process. Finally, SLA printing is a more reliable process than molding and mold making, both of which are sensitive to temperature and humidity changes.

However, SLA could not be a suitable replacement for the current molding process. The surface finish of parts must have few imperfections to photograph well, which may not be possible if supports are required. Another potential drawback is the resolution of the print. Molding can replicate the clay positive precisely. Therefore high resolution is needed.

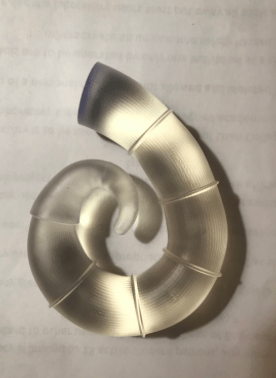

To test SLA printing’s viability for special effects prosthetics, I printed a ram’s horn test prosthetic. I will evaluate it on three main criteria: manufacturing time, surface finish, and resolution. Manufacturing time will be quantitatively compared between methods. Surface finish will be qualitatively assessed. The resolution will be evaluated by comparing the expected size to the actual size of a test feature. Based on these criteria, the ability to print complex geometry and the overall effectiveness of SLA printing will be evaluated.

Evaluation

Time to manufacture

The traditional molding process is time-consuming, with most of the time spent waiting for components to dry. The plaster cast, once applied, takes 24 hours to cure, and foam latex, once poured, takes 6 hours in an oven to cure. Ignoring the time it takes to mold the clay, a minimum manufacturing time of 30 hours.

SLA printing is comparatively less time-intensive. The [50 ml] piece I printed took 8 hours to print, 10 minutes to wash in an IPA bath, and 30 minutes to cure under UV light at 60 degrees celsius, a total manufacturing time of under 9 hours, a third of the time a mold would take

Post-Processing

In addition to the initial manufacturing process, both molding and SLA printing require post-processing steps. For SLA printing, removing the supports took about 20 minutes, which will only increase as a part scales up. While this was time-consuming, the molding process also requires some amount of post-processing. Once removed from the mold, the foam latex pieces will have uneven edges and must be trimmed to ensure that the prosthetic can blend seamlessly with the skin.

Surface finish

A key component to the applicability of SLA printing to special effects prosthetics is its ability to create a smooth surface that will photograph well. As you can see in the pictures below, one side of the SLA ram’s horn (on the right) appears smooth in the photograph with no surface imperfections, but the other side (on the left), where the supports were attached, has many clearly visible surface imperfections.

Unfortunately, the support drastically reduces the quality of the surface finish. The more complex the shape, the more support is required. This means that SLA printing will likely only be viable for very specific geometries that don’t need much support material if any at all.

Resolution

In addition to a smooth surface finish, SLA printing needs to capture detail to a high level of detail to rival the molding process. Capturing fine detail is the main advantage of molding in special effects prosthetics. To evaluate this, I printed 2 mm ridges along the length of my SLA printed ram’s horn and, using calipers, measured each of these ridges. The ridge width varied from 1.40 to 1.79 mm, with an 11 to 30 percent error. While this accuracy will look visually accurate for the most part, it may not be suitable when a specific and small-scale effect, such as texture, is required.

Conclusion

SLA printing offers a huge time advantage over molding, decreasing manufacturing time by about two thirds. SLA printing also offers decently high resolution, enough resolution to visually pass but perhaps not suitable for fine features such as complex textures. The main disadvantage it faces is its ability to produce a good surface finish. Any place a support contacts the part can leave a surface imperfection that will be visible on camera.

It is possible that SLA printing could be a suitable replacement to the mold-making process, but care would have to be taken so minimal support material, if any at all, is used. This limits SLA’s usefulness to parts of specific geometries that require little support, but for those particular parts, productivity drastically increases due to a large decrease in manufacturing time.

Leave a comment